Modifying Restrictions on Bequests: A Changing Landscape

“If only we could modify the restriction on this bequest!” Many charities have voiced this wish, especially with older endowments designed to meet the challenges of an earlier era. (Think of estate plans from the middle of the last century that are now maturing and providing funds to the March of Dimes “to eradicate polio in the United States.”) Less dramatically, current charity leaders may simply believe there is a better use for money than that prescribed by a long-deceased donor.

The law on releasing restrictions is now something of a paradox. Both the old and the quite different new laws remain fully in effect. There is little reason to think this situation will change. This article provides a practical and readable overview of an arcane subject that is of critical significance for bequest managers and the charitable community at large.

Old Cy Pres Donor-Friendly, New Cy Pres Charity-Friendly

In most cases, lifting or modifying restrictions on bequest gifts has required judicial application of the doctrine of cy pres (pronounced “see pray”), shorthand for the French phrase “cy près comme possible” (“so near as possible”). Traditionally, cy pres modifications have been available only when the testator’s gift restriction has become impossible, or virtually impossible, to achieve. Moreover, the revised restriction must mirror the donor’s original intention to the greatest extent possible. This “old cy pres” honors the donor’s wishes but often handcuffs the charity.

Thanks to two widely adopted uniform laws, a more charity-friendly “new cy pres” doctrine has become available in certain cases. The Uniform Trust Code (UTC) and the Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act (UPMIFA) are in force in many states (UTC in more than thirty, UPMIFA in all but one). These enactments allow modifications of restrictions that have become “impracticable” or “wasteful,” as well as those that are impossible or illegal. Modified restrictions need not be “close to” but merely “consistent with” the donor’s original intent. New cy pres allows charities far greater latitude in repurposing gifts but has the potential to eviscerate the deceased donor’s wishes.

Old Cy Pres: Century-Old Restriction Upheld

Old cy pres has not left us. Whether enshrined in judicial decisions or nonuniform statutes, it remains the controlling law when (a) the plaintiff fails to invoke a different standard or (b) the case falls outside the narrow purview of UTC and/or UPMIFA.

A recent example of old cy pres is Matter of Bierstadt Paintings Charitable Trust, 2021 WL 3057076 (N.J. Sup. 2021). The case involved the 1919 gift by a local philanthropist of two significant Bierstadt paintings to the City of Plainfield for the purpose of public display. One of the paintings depicted the Landing of Columbus at San Salvador. The other was a scene in the Sierras.

The city sought permission from the court to sell both paintings, with a price of about $20 million. The application was based in part on the cost of maintaining the works, but mostly because the Columbus painting referenced historical events now considered shameful and, in addition, contained objectionable representations of Indigenous persons. (The Sierras painting was uncontroversial.) The city proposed using the sales proceeds for children’s education programs.

The court declined to grant modification of the century-old gift, citing the donor’s desire for public display of the paintings in Plainfield. A sale might simply move them into private collections, thereby frustrating the purpose of the gift.

The court blocked the requested liquidation as inconsistent with the donor’s wish that the art be displayed. (It was also clear that the planned use of the proceeds was far afield of the original use.) In dicta, the court suggested moving the art into a less prominent place to minimize the risk of offending viewers. Further, the court observed that if the city wished to be free of the financial burden of maintaining the paintings, it could simply donate them to a museum for display as the donor intended.

This case applies traditional cy pres theory to deny the requested lifting of the restriction. To be fair, there are decisions that enunciate the strict cy pres doctrine yet apply a more relaxed standard to avoid draconian results. However, charities cannot count on judicial flexibility when seeking relief. Petitions to relax or remove restrictions on bequests are in many ways a roll of the dice. Decisions in these cases usually favor the donor’s actual intent.

The Bierstadt case is notable for another reason. Neither the applicant (the city) nor the court appears to have considered the fact that the UTC was in effect in New Jersey at the time of this decision. If the city held the paintings in trust, which is quite possible, UTC may have provided the basis for a different decision. Or maybe not. In any event, the Supreme Court of New Jersey declined to hear the city’s appeal of the ruling, so the decision stands. At this writing, the city still owns the paintings.

New Cy Pres: Restriction in Jeopardy

The new cy pres is in play in a pending case that has received significant attention in the media.[1]

The Orlando Museum of Art (OMA) recently found itself in a situation that led it to seek revision of a restricted bequest. The museum was the unwitting victim of a scheme by some organizers of its widely publicized exhibition of hitherto unknown works by Basquiat.[2] The paintings turned out to be forgeries and OMA has suffered a costly fallout. Donor defections and public relations issues ensued. On the financial side, the museum is dealing not only with the loss of its investment in the exhibit but the costs of litigation, response to government subpoenas, and damage control measures.[3] OMA’s cash flow issues have been the subject of several news reports.

For background, the museum received a $1.8 million bequest from the estate of Margaret Young. Young died in 2005, leaving bequests to two of her daughters, with OMA as the residuary beneficiary upon their deaths. The first died in 2023, generating the large gift. Another daughter has a near-identical trust, with a similar benefit expected for OMA upon her death.

Ms. Young’s bequest was restricted to OMA’s “Permanent Collection Fund and used to add to their permanent collection.” For its part, and certainly related to the fallout from the Basquiat incident, OMA would prefer to use the gift “in service of” the permanent collection. The services include “curatorial staff, vault maintenance/repair, [and] security.” This sounds very much like overhead and is nothing like Ms. Young’s desired purpose. There are reports that the surviving daughter is not supportive of the effort to revise her mother’s testamentary instructions.

OMA has asserted that its adherence to Ms. Young’s restriction would be impossible because the museum has no fund named as the “Permanent Collection Fund.” This position seems like semantics since one assumes that art museums exist, in part, to “add to their permanent collection” as Ms. Young desired. Creation of a fund matching the name specified in Young’s gift language appears to be a simple administrative matter and certainly unnecessary for compliance with her wishes.

We suspect, however, that OMA’s denial of the existence of such a fund was part of a larger strategy to support a new cy pres claim filed under UPMIFA. That statute would not apply if the Young funds were “program funds,” so OMA understandably wished to characterize them as institutional or investment funds and not as part of an account reserved to buy new art.

A case under UPMIFA would give OMA at least three guaranteed advantages over traditional cy pres:

- OMA could argue that adherence to the existing restriction would be impracticable during the Basquiat crisis. (It would not need to show “impossibility.”)

- UPMIFA mandates some level of Attorney General involvement in such a case. The Florida AG has gone on record in support of OMA’s application, a factor that may carry significant weight with the court.

- Under UPMIFA, there is little chance that the surviving daughter’s objections will factor into the court’s decision.

Prognostication is always difficult. Without actual case documents, it may be foolhardy. Nonetheless, the competing rationales come down to these two:

- The Case for Application of Cy Pres to Remove the Restriction. The support of the Attorney General could well lead the court to grant OMA’s petition, especially if financial analysis shows that the museum’s survival, or its ability to function in a meaningful way, would be in doubt if the restriction stands. It does no good to support a permanent collection if there is no museum to house it.

- The Case Against the Application of Cy Pres. The biggest obstacle for the museum under either version of cy pres is that the proposed alternate use of the bequest for overhead seems neither close to, nor even consistent with, Ms. Young’s intentions. It is completely different. Every charity knows that donors view program expenses and overhead as opposites, so the alternate use proposed by OMA is quite aggressive. Whether the court is willing to rationalize this difficulty away is the key to this case.

On balance, we suspect that OMA will prevail and that there will be a substantial revision to the restriction. Such a result would be almost unthinkable under old cy pres.

CCK TAKE-AWAYS:

- One way to minimize the likelihood of seeking a revision of bequest restrictions is to encourage known bequest prospects to include modification instructions in testamentary documents. This allows donors an even greater degree of control and permits incorporation of the “impracticability” standard right into the estate plan. For example, “I bequeath $1 million to XYZ for maintaining its current residential facility for cats. If that is impossible or impracticable, the bequest shall be used for other programs benefitting cats.” In the preceding hypothetical case, if the residential facility closed in future years, the modification instruction would eliminate the need for a cy pres

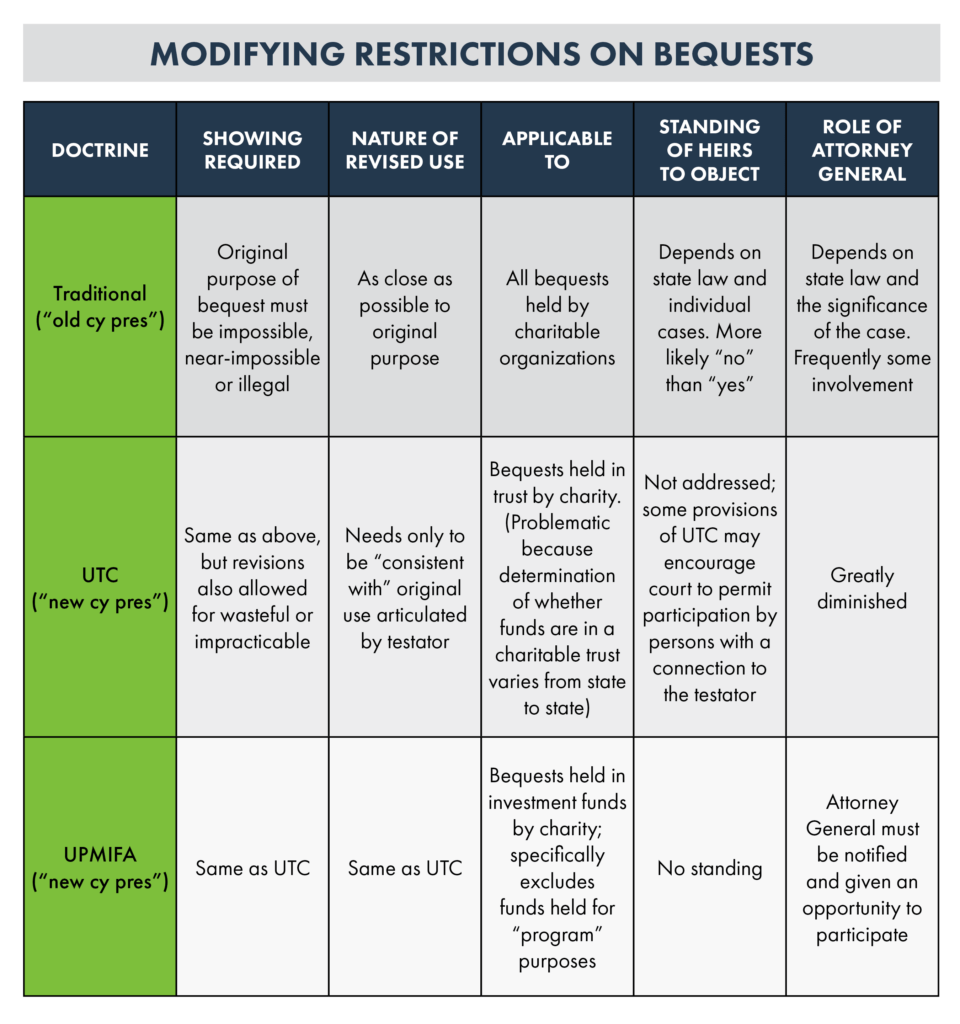

- It is useful for bequest managers to understand the different options available if a cy pres situation arises. The appendix to this newsletter is a quick reference chart on those options as they apply to restricted bequests. Caveat: this is a plain-language basic summary that makes no claim to full exposition or to any capture of the nuanced changes that may exist in a particular state. Nonetheless, it may be a useful primer for an incredibly involved subject of immense importance to charitable organizations.

Endnotes

[1] The filings in this case are “non-public,” so the information comes from multiple reports by reliable sources.

[2] Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), a neo-expressionist painter. His works fetch stratospheric bids ($100 million +) in the art market.

[3] There has been no suggestion of the slightest misconduct by the museum as an institution. The subpoenas simply sought information needed by government teams that investigate high-dollar art fraud. It is possible that one of the museum’s employees conspired with the fraudsters. Litigation between OMA and that (former) employee is ongoing.